"

Just as there are Biennales all over the globe, The Biennial Project has collaborators across the oceans. One of our ‘mates’ is Marlene Sarroff who resides in Australia . Marlene is one of those special artists who just does it. She proved this to us at last year’s Venice Biennale by coming to stay with us, The Biennial Project, without having ever met us in person. She co-habituated with us only knowing our reputation (which might keep the shyer artist away) and instantly became part of The Biennial Project.

Not only did she take the opportunity to witness the best art in the world, get rowdy at the most fabulous parties and brighten up our Villa, Marlene had the good fortune to watch a top international prositute make ‘a date’ on skype right in the middle of the lobby of The Hotel Danelli.

If you think you can handle us, stimulating art, fashionable parties and world class hookers keep reading our blog and our facebook page to see how you can join us and elevate your hip factor by coming to The opening week of The 55th Venice Biennale this June.

Anyhow seeing how important and far-reaching our blog is Marlene wanted to share with you a little of The 18th Sydney Biennial (which also happens to be her hometown). In this article Marlene educates you on Maria Fernanda Cardoso and Ross Rudesch Harley’s MUSEUM OF COPULATORY ORGANS (MoCo) 2012

THE MUSEUM OF COPULATORY ORGANS (MoCo) 2012

by Marlene Sarroff

Cockatoo Island is one of four sites chosen for the 18th Biennale of

Sydney. A small island in Sydney Harbor, steeped in early history, with

large cavernous spaced buildings originally built for shipbuilding and coupled

with remnants of convict history and an undulating topography makes for

intriguing spacial opportunities for artists.

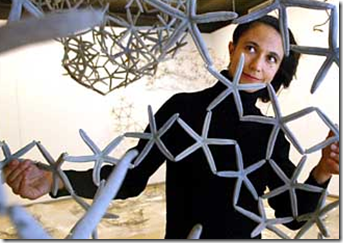

The shipyards former workshops are a perfect museum-like setting to present Maria Fernando Cardosa’s Museum of Copulatory Organs, (MoCo), a selection of scientific models (3D and 2D) and photographs of insect genitalia, together with a film,

Stick Insects most intimate moments.

Originally from Colombia, now living and working in Sydney, she is inspired

by the animal and natural world. She is best known for her flea circus,

whose smallest show on earth became a hit more than a decade ago, when she

discovered the curious yet beautiful plant-like forms in insect genitalia,

which then lead to a PhD at Sydney University on the study of insect

genitalia - The Aesthetics of Reproductive Morphology.

Whilst Cardosa¹s work is placed within the context of art, much of her practice demonstrates a link between the disciplines of art and science. It raises the question of what makes this art and not science? It is perhaps largely a matter of framing the work in the context of such an exhibition.

Evolution has made this collection of dazzling shapes and reproductive devices, however, it takes the artist to make it become visible.

Along with collaborator Ross Rudesch Harley, Cardosa has created an

orthodox natural history museum encompassing her entire collection of

objects -featuring scientific sculptures modeled from glass, metal and

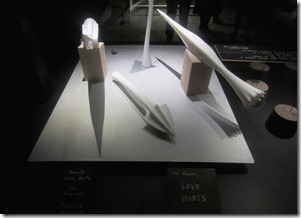

waxy 3D printed resin. MoCo’s extraordinary pieces are created using

scanning electron microscope imaging to magnify and photograph the tiny

appendages.

These black and white photos, which are a part of the exhibition

are then transformed into large resin and glass sculptures. Cardoso and

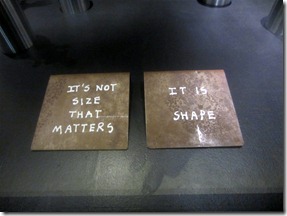

Harley understand the humorous aspect to their work. The exhibitions title

references the male obsession with penis size and is intentionally

provocative, playful and ultimately true in relation to insects.

They invite the viewer to consider the beauty of these sculptural forms, rendered

with scientific precision as they exist in nature. The collection of the

insect genitalia, featuring reproductive tracts and penises is wide ranging

from the beautifully modeled insect and snail spermatozoa, sex organs of the

female fruit fly, to the penis of the daddy-long-legs. The viewer would not

be mistaken in thinking that a lot of animal species are promiscuous,

especially insects and some species which often compete with each other - their

penises including hooks to remove sperm from previous matings.

Video work and 3D prototypes displayed on small LCD displays are part of new media artist Harley’s contribution.

The vast collection has been accumulating over several years of study. It is

not hard to understand the artist¹s fascination with the subject: a close

examination of these miniscule organs reveals an endless morphological

variety - all serving a function, including ensuring successful attachment.

The installation gives us insights into worlds known only to scientists and our

perception is compounded by the unbelievable, yet exotic display of nature

as we have never seen it before. ‘It is a celebration of the diversity of

life’ Cardosa says.

Artist Statement: Maria Fernanda Cardoso

Genitalia are confined to the last two segments of the abdomen, and flea

copulation has been hailed as one of the wonders of the insect world. The

male, normally much smaller than his mate, slides beneath her from behind,

embraces her back-to-belly with his antennae and softly caresses her

genitalia. Then his tail curls up like a scorpion¹s and he penetrates her

with what Brendan Lehane calls the most elaborate genital armature yet

known. The male, he writes, possesses two penis rods, curled together like

embracing snakes. Inside his body, the smaller rod moves outwards lambently,

catching delicate skeins of sperm and moving it into a groove on the larger

longer rod. Then the whole phallic coil slides out from this sensitive rear,

the large rod enters the female and guides the thinner along beside it. The

thin rod continues inwards, eventually depositing its sperm and withdrawing.

Any engineer looking objectively at such a fantastically impractical

apparatus would bet heavily against its operational success writes

entomologist Miriam Rothschild, the astonishing fact is that it works.

There you go - everything you always wanted to know about insect copulation!

XXOO, The Biennial Project

"