The gang of Exceptionally Cool Biennial Project Artists that have just returned from our exhilarating trip to Venice for the press preview week of the Venice Biennale have each agreed to write for you about one exhibit that they really liked - proving that we artists can use our words too (sometimes anyway!). Here's What We Saw, What We Liked - Part One.

RUSSIAN PAVILION, by Charlene Liska

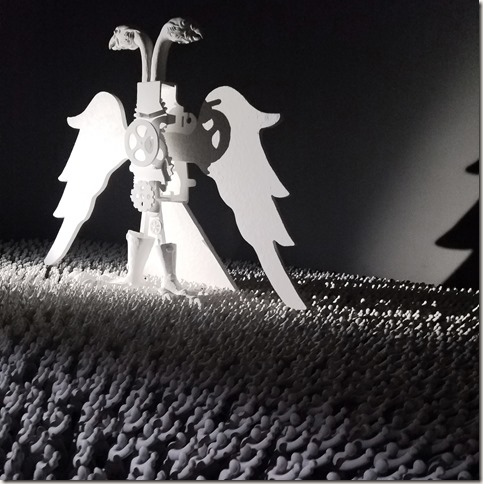

"No two people see the same Biennale, given the several thousand exhibits. Venice is momentary, fragmentary, a hope of chance sights that will hold fast in memory," says Laura Cumming of The Observer. So, stuck in my memory along with a handful of other exhibits (notably several wonderful uses of water and sound) is the Russian pavilion's ‘Theatrum Orbis,’ which references the first modern atlas. With the ambitious aim of spanning the world, the show features three separate pieces on 3 levels, by Grisha Bruskin, Recycle Group, and Sasha Pirogova. Of the three, I was particularly blown away by 'Scene Change' by Grisha Bruskin. It's a marvel of what you can do with black and white, what worlds it can span, how much more expressive and emotionally challenging it can be than ordinary color. In a darkened, domed space, white statues, some archaic, some surreal and futuristic, ring the walls, alternately harshly illuminated in raking light and plunged into darkness. Projected over and above the statues is a richly black and white animation of marching automatons, beginning with one individual, increasing to a horde, ultimately swarmed by fanciful airborne devices. Sound builds from a low murmur to shouts, roars, engine noises, finally to an hypnotic din. Are these multitudes contemporary freedom-fighters? Fascist brigades? Futuristic automatons? It is a deafening, mysterious, and sinister tour de force. In 'Scene Change', per Bruskin, "there is no movement whatsoever, be it from old to new, from primitive to complex, or from worse to better". What I love about this piece, with its great beauty and visceral allure that simultaneously attract and repel, is that it is also a sly reminder that such aesthetic thrills can cut both ways between sublime swoon, innocent enthusiasm ("Go team!"), and Riefenstahl-like enchantment. It's very old, but it's all still in there.

FINNISH PAVILION by Wayne Chisnall

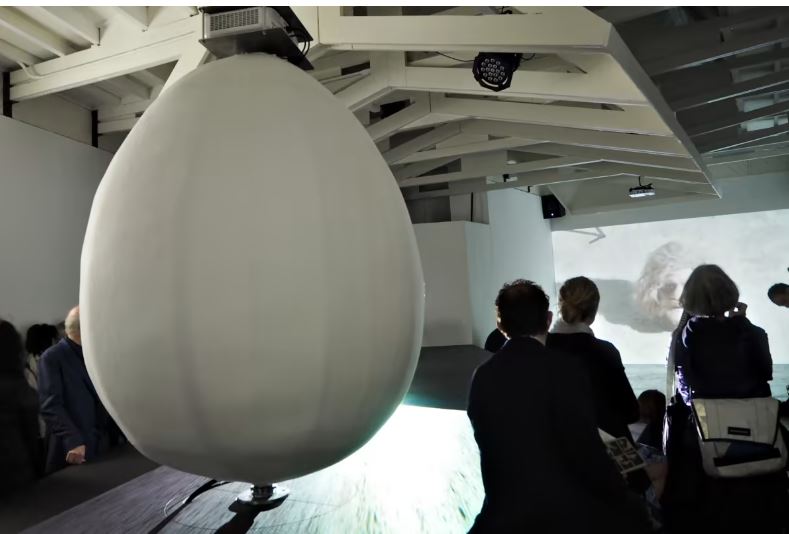

photo by Satu Nurmio / Yle

Re-imagining Finish society, and its stereotypes, through the eyes of two terraforming higher beings (Gen and Atum), Nathaniel Mellors and Erkka Nissinen provide the comedic highlight of this year's Venice Biennale. Unlike many a video installation, where three minutes can feel like three hours, their almost an hour-long piece, The Aalto Natives, leaves you wanting more. Much of this is down to the fact that the video element of the installation (there's also a delightful animatronics element) follows a traditional, if somewhat odd ball, narrative. Occupying a space somewhere between The Mighty Boosh, The Hitch Hikers Guide to The Galaxy, and a demented version of The Muppet Show, Mellors' and Nissinen's satirical sci-fi fairy tale will leave you smiling long after you've forgotten the majority of what's on offer at Venice Biennale 2017.

waynechisnall.com flickr.com/photos/waynechisnall instagram.com/WayneChisnall twitter.com/WayneChisnall

CZECH AND SLOVAC PAVILION by Rob Mackenzie

Rebounding from the political tone of recent Biennals, curator Christine Macel titled the 57th iteration "Viva Arte Viva," remarking, "It’s about art by artists for artists." But the show has always been about what artists want to say to each other and to the world. Jana Želibská’s installation at the Czech/Slovak Pavilion in Giardini speaks plainly about reflection and hope in the face of imminent political and ecological cataclysm.

Entering her pavilion one detours around a container jammed with flotsam. Inside, an array of luminous swans rests placidly on neat islets of coiled rope, backed by a projection of restless waves.

Like so many other voices here celebrating the art that makes us human, Želibská defines apocalypse as "a revealing of mysteries that brings a radical change in the ordering of the world," as she puts it. But her title, Swan Song Now, amid the continuing exodus of Venetian locals from their sinking ship, speaks more loudly, less hopefully.

rmackenzieart.com

GREEK PAVILION by Nick DI Stefano

Can the old and the new live together? Should tradition or the familiar have to make way for progress and the uncertainty that comes with it? Addressing current global sociopolitical issues (with a backdrop of ongoing refugee crises, rising nationalistic and partisan politics, and the economic issues of Greece and the EU at large) the work deals with the anguish and confusion of individuals and social groups when called upon to address similar dilemmas. Presenting viewers with the arguments, the onus is on action. With a classic yet efficient plan, artist George Rivas turns the Greek pavilion into an allegory of today’s scientific, geopolitic and demographic issues with a clear allusion to migratory flows.

Part of a collection of interactive pieces presented at the Biennale, George Drivas’ Laboratory of Dilemmas draws on the structure of ancient Greek drama and is presented on screens and as audio through an installation divided into three parts: the Upper Level, the Lower Level/Labyrinth and the Screening Room. The narrative and installation are based on Aeschylus’ theatre play Iketides (Suppliant Women), written between 463 and 464 BC and the first known literary text to reflect on the issues of a persecuted group of people seeking asylum.

The Suppliants, having left Egypt to avoid marrying their first cousins, arrive in city of Argos and seek asylum from its King. The King’s dilemma is central to the play: CONTINUE READING HERE

GEORGIAN PAVILION by Anna Salmeron

photo by Paul Weiner

Living Dog Among Dead Lions "While someone is among the living, hope remains, such it is better to be a living dog than to be a dead lion." Ecclesiastes 9:4.

I have one rule about looking at art, and that is to always look at it first. Only if I like something about it I will then proceed to the artist's statement. Of course I know that art can be deepened by words of explanation, but call me old-fashioned in insisting that no amount of grad-school parlance can conjure something into being from work that is not compelling on it's own.

This rule has served me especially well at the fire hose of art that is the Venice Biennale, where one must have some kind of system to have any hope of progressing through such a bewildering amount of work. Artistic projects large and small (mostly large) come flying by so furiously that one can be forgiven for wondering if the resurrection itself might pass by unnoticed in such an environment. But then again, any kind of resurrection worth seeing would be able to get your attention anywhere, wouldn't it?

Of course it would. Faith, ye pilgrim.

And so it was that while winding my way through the seemingly unending procession of art installations that is exhibited in the Venice Arsenale during the Biennale, I suddenly came upon this house. This sad old rundown broken-hearted hill house, someplace where all your sad old rundown brokenhearted ancestors toiled and dreamed and then, well, died. A house that is is pitch perfect in it's melancholy evocation of life and loss. And in a masterful inversion of all the adolescent let's-play-with-water-because-it's Venice-after-all-and we-are-so-you-know-site-specific (here's looking at you Canadian Pavilion), it is raining inside the house. Nice and sunny and prosecco-laden outside, but raining forever inside the little house. Forever, or for at least for the six months that the Venice Biennale runs. You can smell the rich earthy decay already, and this was just the first week. What's more, whoever brought us this delightfully doleful house of perpetual rain clearly welcomes us here, because they have provided wonderful little step ladders around the house so that we can climb up and peep in the windows, and look and smell and hear in the rain that sacred elegiac music that is always playing just outside the reach of our conscious minds. l love this doomed and sweetly mournful little house, which speaks such volumes on the wounds we live with deep inside. I will gladly read whatever words this artist has for us.

More sweet surprises! The words are wonderful. Almost as lovely as the house itself, which is the work of Georgian artist Vajiko Chachkhiani, and is Georgia's official contribution to this Venice Biennale. The brochure which accompanies the installation is dedicated to an interview with the artist, and in it one learns that he had the idea for such a house and went searching in the Georgian countryside until he found the perfect abandoned property up in the mountains. He brought the entire house to Venice where he re-assembled it along with all it's original furnishings. The interview is as direct and wise and unpretentious as the work - extraordinary for an artist who is only 32 years old. He must be an old soul. I am happy he is young in this life though, because that means that with luck we can follow his work for years to come. In the meantime, I'm out to walk my beloved live dogs in a nourishing spring-time rain.

AUSTRIAN PAVILION by Holly Howe (OK, we're cheating a little here - she's an actual journalist - but a really arty one.)

While you may not initially "see" the link between Erwin Wurm and Brigtite Kowanz, the two artists that curator Christa Steinle paired for this year's Austrian Pavilion, upon visiting the pavilion you literally see it.

While Wurm’s contribution to the pavilion is predominantly in the form of his “One Minute Sculptures” (which are celebrating their 20th anniversary this year), Kowanz’s “Infinity and Beyond” series comes in the form of neon writing placed on infinity mirrors. The link between the two? Temporality and viewer interaction.

Kowanz has said before in interviews that she’s happy for people to take selfies in her work (the bane of all art with a reflective surface), but even if they don’t, the act of looking at the work places the viewer within it while they look at it.

Wurm is more prescriptive with his sculptures, and the viewer is given instructions on how to pose with each piece, and which posture to adopt. The results are often amusing – on the opening morning, some visitors thought the models were wax dummies as opposed to living people – but in an interview with The Collectors Chronicle, Wurm stated “the assumption that my work is predominantly humorous is wrong.” Instead, he is more interested in the relationships between the objects in the gallery and how the viewers interact with them to create new objects.

Personally, I din't find Kowanz's work particularly new or engaging. Whereas Wurn's I loved, despite it being the continuation of an existing series. And what capped it off was the opportunity to climb to the top of an inverted truck outside the pavilion, and gaze at Venice. Even though Wurm's cheeky guidance was to "stand quiet and look out over the Mediterranean Sea". Which obviously isn't on view...

instagram.com/hollytorious

LUXEMBOURG PAVILION by Markus Blaus

The Luxembourg Pavilion is famous with The Biennial Project and the rest of the throngs of hungry art-lovers that mob Venice during the opening week of the Biennale as being absolutely the most generous with their receptions – predictably providing an opulent opening night spread for a huge crowd that includes with not only the de rigueur endless supply of procecco, but full dinner and desserts as well.

This Biennale I was fortunate enough not only to eat and drink on their dime but to also speak at some length with the artist and with the curator of the exhibit.

The curator explained that the artists under consideration were first pruned down to a list of twenty five, then three, and that then the top three were invited to give an hour and a half presentation of their ideas to the judges. They wanted not only innovative ideas that represented Luxembourg but also a new youthful vision with a global perspective. The artist they chose, Mike Bourscheid, is 35 years old and currently lives in Vancouver Canada.

His installation consists of 5 rooms. Each room displays costumes the that artist wears during his performance pieces. One room feels much like a mash up of a sport teams locker room and a ballet studio. In it you will find many outfits consisting of heavy-looking leather aprons and large metal cage-like shoes.

Each of these “uniforms” has a number on it. These costumes represent personal connections for the artist. One had the number of his old soccer uniform as a kid. One was that of a former roommate. One was that of Wayne Gretzky the famous hockey player (99). Mike explained that this uniform also represented another hockey legend (whose name, symbolically enough, I can’t remember) who wore the number 9 and who spent his live accumulating enough goals to finally break the goal for the most goals in a career, only to have Sir Gretzky beat his record in only a few years. During his performance piece for this uniform the artist uses a pony tail to cover one of the 9’s to transform from one of the hockey players to the other.

In another room viewers are required to put protective covers on their feet before walking on the carpet although the carpet is not in any way special. The act of putting covers on one's feet involves the viewer in the experience of putting on a costume and contributes to an overall vibe of viewer-friendly and playful performance that makes the Luxenbourg Pavilion a Biennial Project favorite (and not only for the quality of the vittles!).

OK, that should do it for What We Saw, What We Liked - Part One. Part Two up next! Check out our blog, website and facebook page for more on Venice!

Some of the Biennial Project Gang in Venice photo by Paul Weiner