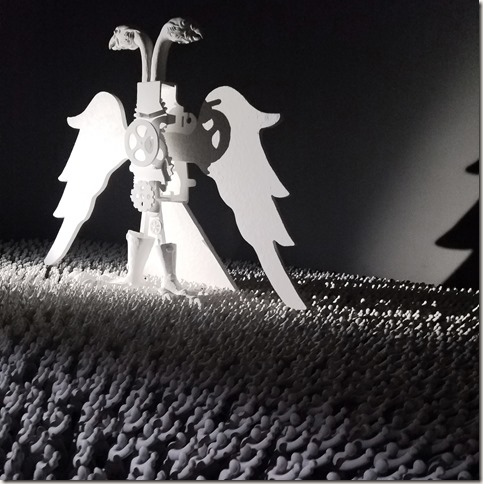

"No two people see the same Biennale, given the several thousand exhibits. Venice is momentary, fragmentary, a hope of chance sights that will hold fast in memory," says Laura Cumming of The Observer. So, stuck in my memory along with a handful of other exhibits (notably several wonderful uses of water and sound) is the Russian pavilion's ‘Theatrum Orbis,’ which references the first modern atlas. With the ambitious aim of spanning the world, the show features three separate pieces on 3 levels, by Grisha Bruskin, Recycle Group, and Sasha Pirogova. Of the three, I was particularly blown away by 'Scene Change' by Grisha Bruskin. It's a marvel of what you can do with black and white, what worlds it can span, how much more expressive and emotionally challenging it can be than ordinary color. In a darkened, domed space, white statues, some archaic, some surreal and futuristic, ring the walls, alternately harshly illuminated in raking light and plunged into darkness. Projected over and above the statues is a richly black and white animation of marching automatons, beginning with one individual, increasing to a horde, ultimately swarmed by fanciful airborne devices. Sound builds from a low murmur to shouts, roars, engine noises, finally to an hypnotic din. Are these multitudes contemporary freedom-fighters? Fascist brigades? Futuristic automatons? It is a deafening, mysterious, and sinister tour de force. In 'Scene Change', per Bruskin, "there is no movement whatsoever, be it from old to new, from primitive to complex, or from worse to better". What I love about this piece, with its great beauty and visceral allure that simultaneously attract and repel, is that it is also a sly reminder that such aesthetic thrills can cut both ways between sublime swoon, innocent enthusiasm ("Go team!"), and Riefenstahl-like enchantment. It's very old, but it's all still in there.

Charlene Liska, for The Biennial Project