by Barbara Jo Revelle

Ok, I’ll admit this up front. I’m wildly attracted to durational performance art. I do it myself sometimes. Not so long ago, as part of an art installation scrutinizing my father’s big game hunting practice, I walked continuously - eight hours a day, seven days a week, for two weeks - on a treadmill set up in a gallery. I stopped only to take pees. While I moved I edited 100+ hours of my father’s old hunting films and videos - mostly shots of him watching game from blinds, hanging cut up animal parts baits in trees, or posing with dead animals and the African natives who helped him track and kill them. This footage was projected onto the gallery walls in front of me as I walked and worked.

I was trained as a photographer and filmmaker but there has often been at least a nod to durational performance in my own art projects. In the late 1970’s, more than half a lifetime ago, when I was just getting serious about art making and was traveling from San Francisco to Belize, I did a 91-day durational performance called Reading. The rules I gave myself included traveling only at night, reading the local newspaper from whatever town I woke in each day, and then spending whatever was left of the morning reading art theory. At noon I stopped reading and used the rest of the daylight hours trying to track down and photograph whatever was referenced in the news, using whatever strategy the theory readings had inspired. My “tracking” activities got me into all kinds of trouble, legal and otherwise. The resulting exhibition at the San Francisco Art Institute consisted of 91 columns of my daily photographs, a diaries, maps, the front pages of each newspaper and xeroxes of the art theory hung so that viewers could take each text off the wall and read it.

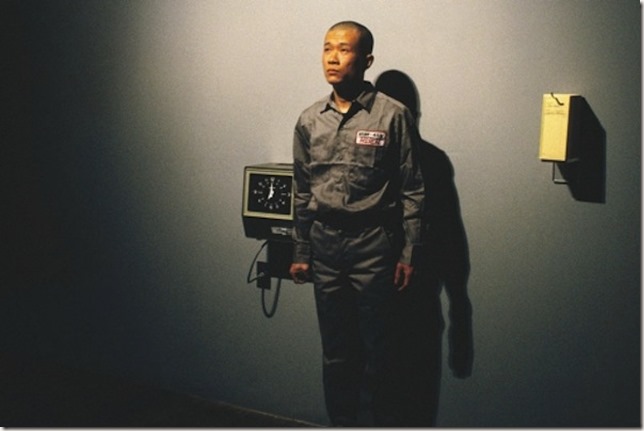

So, yeah. No big surprise that the artist I loved the most in all the dizzying array of projects and spectacles at the 2017 Venice Biennale was Tehching Hsieh in the Taiwanese pavilion. Hsieh is the quintessential endurance artist. In this exhibition “Doing Time” various documents, maps, charts, films, photos and artifacts evidenced two of his monumental ‘One Year Performances’. In one (Time Clock Piece, 1980-81) he clocked onto a worker’s time clock on the hour, EVERY hour, for the entire year. Talk about extreme measures, abjection, suffering, and survival through adversity? Wow! Each time he punched the time clock a movie camera shot a single frame. The film went by in about 6 minutes. You could see his hair grow and the effects of extreme sleep deprivation worsen, but mostly you just had to imagine what it might be like to do something that insane to your own body. Hsieh makes other endurance artists look like pleasure seekers by comparison. Was this piece intended as a metaphor about labor? How selling your time cuts into one’s sense of self as a sentient being? Was this a politically inflected critique of routinized labor practices? Capitalism? Over the top masochism? WTF was this event? What did it mean to do something like this? By comparison, all this year’s other Venice sights paled (even Damien Hirst’s mind-boggling, two-museum embarrassment, even Roberto Cuoghi’s crazy Jesus-statue-factory in the Italian Pavilion.)

“Endurance art” AKA “durational performance art” arguably started in about 1971 with Chris Burden (who taught at UCLA and who had an office right next door to mine… who also famously had his hands nailed to the roof of a Volkswagen Beetle in an artwork he called “Transfixed”). Before any of this he did his MFA thesis by locking himself into a small school locker for five days and nights. In the locker above his he placed a five-gallon bottle of water to drink, attached to his locker with a hose. In the locker below him was another five-gallon bottle, initially empty. That’s all.

A bit later others did similar strange things in the name of art. In 1974 the German artist Joseph Beuys, wrapped in his signature felt, had himself delivered by ambulance to a NYC gallery and subsequently caged in with a wild coyote for seven days and nights.

Today there are many venues, shows, journals and whole conferences devoted to durational performances. Scores of artists have become famous and infamous doing them. In The House with the Ocean View (2003), Marina Abramović lived for 12 days without food or entertainment, in total silence, on a stage entirely open to the audience. Since that time she has done all kinds of similar pieces culminating in the Artist is Present, 2010, Museum of Modern Art, NY, where she sat opposite museum visitors for eight hours a day, without speaking, for a total of 750 hours. She and her one-time lover Ulay, after they decided their relationship had run its course, each walked the Great Wall of China starting from opposite ends. They met in the middle and hugged goodbye. Poetic way to end a relationship, right?

Sometimes this kind of duration performance activity is called “time based art” or “endurance art” but whatever you call it, I’m in love with it. Lately I’ve been trying to figure out WHY. I swim laps daily, do some open-water, charity, distance swims, and have always been interested in discipline, stoicism and the like, but I think it’s more than that. What I really love about this kind of work is the impulse to do art that is not about making money, artwork that comes from some instinct that is the opposite of the intent to make art for the market. So much of the art world these days (art fairs, auctions, galleries, etc.) has become the playground of status seeking new millionaires and billionaires. So when I encounter artists who define art as experience, something by which one might be transformed, opened up, changed … well, I get excited. I remember why I wanted to be an artist in the first place. Now that I’m old (I’ll be 71 in four days) and retired from teaching, I do a lot of wandering and drifting around galleries, art fairs and biennales. I notice what most attracts me is work that raises questions about time, life, being … work that has conceptual purity and maybe even physical extremity.

For me, no other artist, not Abramović or Burden or even Emma Sulkowicz, the controversial student-artist who dragged a fifty pound mattress all over Columbia’s campus to make a point about rape, has made work with anything like the power, poetic reach or disturbing resonance of Tehching Hsieh’s high-stakes performances.

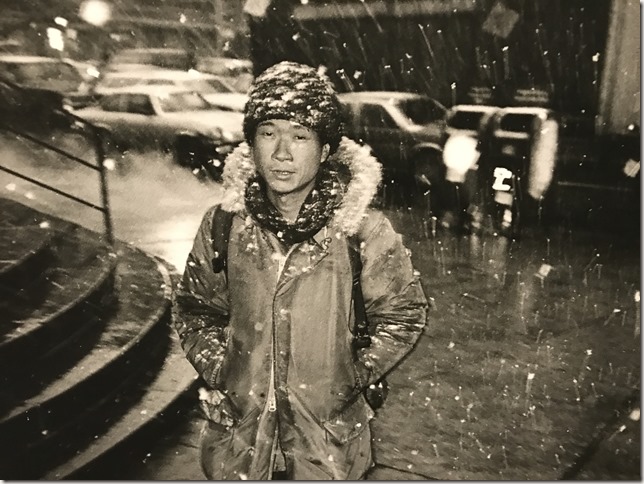

In the second one-year performance (“Outdoor Piece”) featured at the Taiwanese pavilion, work made in 1981/82, Hsieh took deprivation and resourcefulness to a whole new level. In that project he remained outside for a year without taking shelter of any kind (no cars, no trains, no tents). He did this in the streets of NYC in a year that was one of the coldest winters in history. The documents of his performance, photos of him crouching against a wall or sleeping near a fire in a trashcan, just show him surviving. You get to see only what he wore, what he carried, his sleeping bag, his backpack, how dirty and ‘unkempt’ he became. All the ingenuity, stoicism, and empty time on his hands is just implied, and there are only traces, haunting indexes, to answer the questions that arise in the viewer’s mind when contemplating the work. How did he feed himself? What did he think about? What did he DO all day? See? Was he afraid? In pain? How did he manage not to freeze to death? Did cops harass him? Was this event a Zen Buddhist influenced meditation? A metaphor? For what? Was he happy? Radically forlorn? Was the work about homelessness in a political sense? About fear of being incarcerated? Since Hsieh was an illegal immigrant at the time he did the project, and was not granted amnesty until 1988, his act of living by his wits in a big city, with only what he could carry on his back, resonates even more strongly in these heartless post-Brexit/Trump times, given the crisis faced by an estimated 65 million refugees in the world at this moment.

Hsieh did three other yearlong performances, five in all. His first, in 1978, consisted of him locking himself in a cage and not speaking, reading, watching TV or writing for a year. Later he and Linda Montano performed a collaboration whereby an eight-foot length of rope bound the two artists to each other 24 hours a day for another whole year (from July 4, 1983 to July 3, 1984). One of the rules was that they could not touch each other.

Lastly, in 1985-86, Hsieh did a yearlong performance with the single rule that he would stop making, seeing, reading about, talking about, or listening to anything about art. Now on the surface of it, a gesture like this might seem anticlimactic, but if you think about how intense had been his other four “one year performances”, doesn’t this art-free year just amplify the questions raised by all his prior practices and experiments? How is ‘art’ like - and unlike - ‘life’? What should one do with one’s time on earth? What IS time? How is freedom related to entrapment? What IS freedom?

Additionally, since Hsieh, by the time he did this art-free year performance, had become “a well-known name” (read famous!) in the New York art scene, his fifth yearlong performance seems to be about becoming invisible again. I can’t think of a more radical way to challenge the commodification of art then to stop not only buying it, but to stop seeing it, talking about it, reading about it and making it. Keep in mind that the definition of commodification is the transformation of goods, services, ideas (and not least people) into objects of trade. Are artists - are people - turned into objects by selling their labor to the marketplace? For me Hsieh’s last one-year performance “No Art Piece” is about these root questions.

(Barbara Jo Revelle is an artist and educator living in Gainesville Florida. She is Professor Emeritus and former Director of the School of Art and Art History at the University of Florida.)

[EDITOR’S NOTE – She is also just the coolest, smartest, most insanely fun and talented individual imaginable, and we are so damned lucky that she’s willing to run with us.]

barbarajorevelle.com